When you look at a landscape painting, it’s easy to think you’re just seeing trees, mountains, and sky. But behind that calm scene is a carefully built structure-three key parts that give depth, balance, and realism to the whole piece. These aren’t just artistic choices; they’re the foundation of how painters trick your eyes into seeing space on a flat canvas. Master these three components, and you’ll start seeing landscape paintings the way artists do.

Foreground: The Closest View

The foreground is what you’d see if you stepped forward in the painting. It’s the part closest to the viewer, often placed at the bottom third of the composition. This area anchors the scene. Without it, the painting feels like it’s floating.

Artists use the foreground to draw you in. A winding path, a cluster of rocks, a fallen log, or even footprints in the dirt-all of these elements pull your eye from the edge of the canvas into the deeper space. In John Constable’s The Hay Wain, the shallow water and muddy bank in the foreground don’t just show the river’s edge-they make you feel like you’re standing right there, boots in the dirt.

Texture matters here. Rough brushstrokes, thick paint, and sharp edges work best in the foreground because they mimic how things look up close. Colors are usually more saturated too. A green bush in the foreground might be a vivid emerald, while the same bush in the distance turns duller, bluer, and softer.

Middle Ground: The Storytelling Zone

If the foreground is the doorway, the middle ground is the room. This is where most of the action happens. Trees, buildings, rivers, roads, and figures often live here. It’s the bridge between what’s near and what’s far.

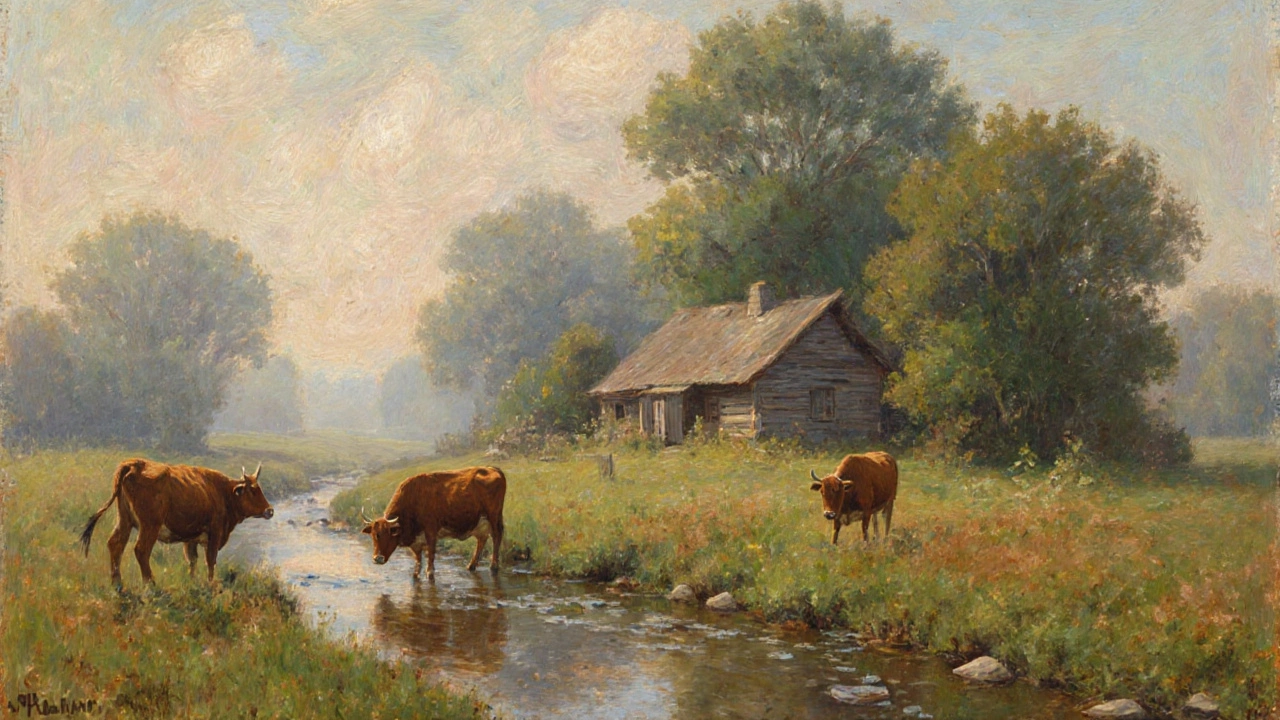

This layer gives the painting its narrative. A farmhouse nestled among trees, a group of cattle grazing near a stream, a distant bridge crossing a valley-these are the details that tell you what kind of place this is. Is it rural? Peaceful? Abandoned? The middle ground answers those questions without words.

Painters control the middle ground with value and detail. Colors soften compared to the foreground. Edges blur slightly. Brushwork becomes looser. A tree in the middle ground might have visible leaves, but they’re not individually painted-they’re suggested with dabs of green and ochre. This creates the illusion of distance without losing clarity.

Many beginners make the mistake of filling the middle ground with too much detail. That clutters the space and kills the sense of depth. The trick? Less is more. Let the viewer’s mind fill in the rest.

Background: The Breath of the Scene

The background is the sky, the far mountains, the hazy horizon. It’s the quietest part of the painting-but also the most important. Without a strong background, the whole scene feels shallow, like a cutout stuck to a wall.

Atmospheric perspective is the secret here. As objects get farther away, they lose contrast, color intensity, and detail. Blue and gray tones dominate. A distant hill that’s green up close becomes a soft lavender-gray when it’s miles away. That’s not reality-it’s how light and air change what we see.

In Turner’s Rain, Steam and Speed, the background melts into mist and sky. The train is barely a shape, the bridge a suggestion. Yet you feel the storm, the speed, the vastness. That’s the power of a well-painted background. It doesn’t need to be detailed-it needs to feel infinite.

Many painters leave the background almost empty. A wash of diluted paint, a single horizontal line for the horizon, a hint of cloud. That’s enough. Overworking the background turns it into noise. Let it breathe.

How the Three Work Together

These three layers don’t exist in isolation. They depend on each other. The foreground gives you a place to stand. The middle ground gives you something to look at. The background gives you somewhere to look toward.

Think of it like a camera lens. The foreground is the focus point. The middle ground is the context. The background is the out-of-focus blur that makes the whole image feel three-dimensional.

When all three are balanced, the painting feels natural. When one is missing, it feels off. A painting with a strong foreground and background but no middle ground? It’s like a photo with nothing in the middle-sudden, jarring. Too much detail in the background? It competes with the foreground and confuses the eye.

Try this: take any landscape painting-Claude Lorrain, Thomas Moran, even a modern watercolor-and trace your finger from the bottom to the top. Notice how the texture changes. How the colors shift. How the detail fades. That’s the rhythm of depth.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Even experienced painters slip up. Here are the three most common errors:

- Flattening the scene: Putting everything at the same level. Trees, hills, and sky all painted with equal detail. Result? A cardboard cutout.

- Overdoing the foreground: Painting every blade of grass, every rock crack. It overwhelms the eye and makes the rest of the painting feel small.

- Ignoring atmospheric perspective: Painting distant mountains with bright greens and sharp edges. That’s not distance-that’s a mistake.

One quick fix? Squint your eyes while looking at your painting. What disappears? That’s what should be softened in the background. What pops? That’s your foreground. Use that as your guide.

Practical Exercise

Grab a blank sheet of paper. Divide it into three horizontal sections: bottom third = foreground, middle third = middle ground, top third = background.

Now, sketch a simple landscape using only shapes:

- Foreground: Draw two or three rough shapes-maybe a rock, a bush, a path.

- Middle ground: Add one or two simple structures-a tree, a cottage, a stream.

- Background: Just a horizon line and a hint of hills or sky.

Don’t add color yet. Just get the structure right. Then, look at it. Does it feel deep? Or flat? Adjust until the eye moves naturally from front to back.

This exercise takes five minutes. But it teaches you more than hours of copying photos ever could.

Why This Matters Beyond Technique

These three components aren’t just for painters. They’re how humans naturally see the world. We don’t stare at a flat picture. We move our eyes through space-close, then middle, then far. Landscape painting taps into that instinct.

When you understand this, you don’t just paint better. You see better. You notice how a real forest has thick underbrush near you, scattered trees in the distance, and mountains fading into the haze. That’s not just art-it’s observation.

Great landscape painting isn’t about copying nature. It’s about organizing it. The three components are the rules that turn chaos into calm. Master them, and you’re not just painting a scene-you’re building a world.

What are the three major components of landscape painting?

The three major components are the foreground, middle ground, and background. The foreground is the closest part to the viewer, often featuring detailed textures and vibrant colors. The middle ground holds the main subject-trees, buildings, or figures-and provides context. The background includes distant elements like mountains or sky, rendered with soft edges and muted tones to create depth through atmospheric perspective.

Why is the foreground important in a landscape painting?

The foreground grounds the painting and draws the viewer in. It’s where texture, contrast, and detail are strongest, making the scene feel tangible. Without it, the painting lacks depth and feels disconnected from the viewer’s space. Elements like paths, rocks, or grasses in the foreground act as visual entry points.

How do you paint the background to show distance?

To show distance, use atmospheric perspective: reduce contrast, lower color saturation, and soften edges. Distant objects should appear lighter, bluer, and less detailed. A green hill far away might become a pale gray-blue wash. Avoid sharp lines or bright colors-they break the illusion of depth.

Can a landscape painting work without a middle ground?

Technically, yes-but it won’t feel complete. The middle ground provides narrative and balance. Without it, the painting jumps from close-up details to distant haze, creating a visual gap. Most successful landscapes use the middle ground to anchor the story-whether it’s a house, a river, or a group of trees.

What’s the biggest mistake beginners make with landscape composition?

The biggest mistake is treating all parts of the painting with equal detail. Beginners often paint every leaf, every rock, and every cloud with the same intensity. This flattens the scene. Depth comes from variation: sharp and detailed up front, soft and simplified in the distance.