When you walk into a gallery and see a jumbled mix of canvases, installations, and digital screens, you might wonder: how do you classify modern art? The answer isn’t a single formula, but a toolbox of lenses that art historians, curators, and collectors use every day. Below you’ll find a step‑by‑step guide that helps you sort artworks by time, style, medium, and cultural context, so you can talk about them with confidence.

Key Takeaways

- Modern art spans roughly 1860‑1970 and is divided by movements, media, and geography.

- Chronology, style, technique, and cultural context are the four main classification pillars.

- Use a quick checklist to place any artwork within these pillars.

- Watch out for overlapping movements and post‑modern reinterpretations.

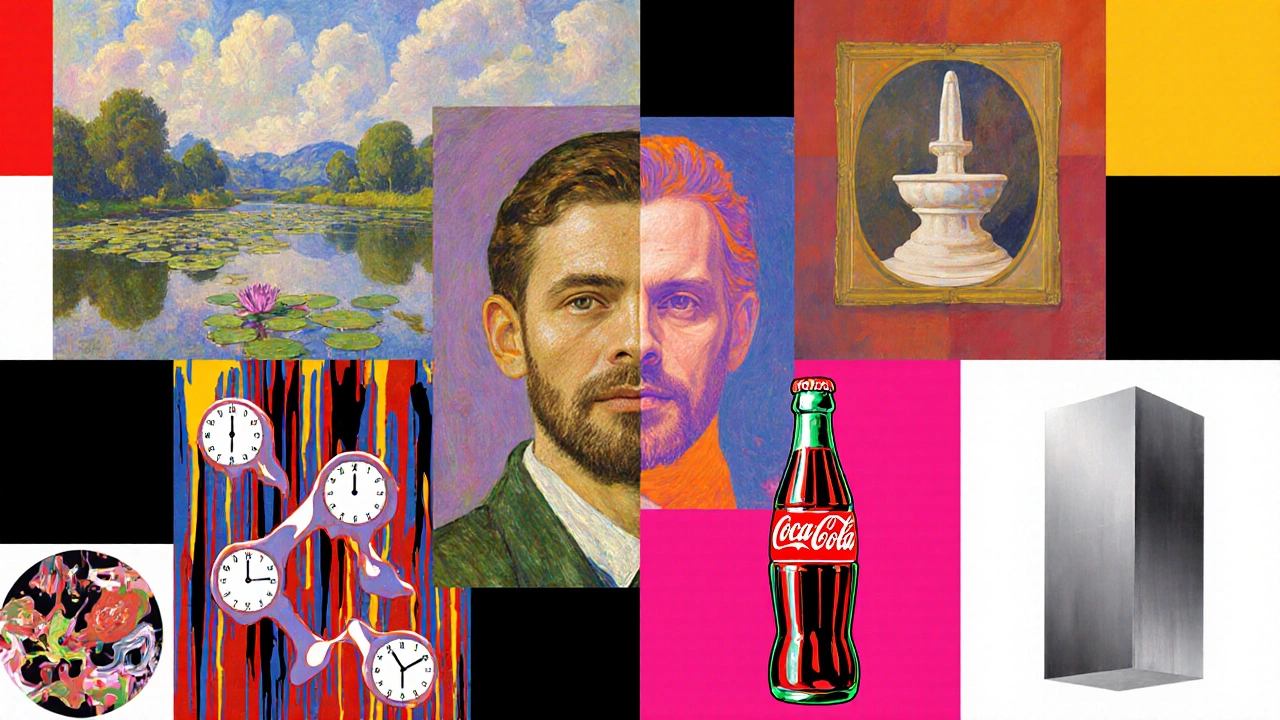

- Practical examples-like a Monet landscape or a Warhol print-make the system tangible.

Modern Art is a broad period in art history that emerged in the late 19th century and stretches to the mid‑20th century, characterized by a break from traditional representation and an embrace of experimentation. It includes dozens of movements, each with its own philosophy, visual language, and key figures. Understanding how to slot an artwork into this mosaic helps you appreciate its meaning and market value.

Why Classification Matters

Classification isn’t just academic jargon; it serves three practical purposes. First, it provides a shared vocabulary that lets you discuss artworks with others-whether you’re in a museum, a classroom, or a bidding war. Second, it aids provenance research: knowing an artwork’s movement can narrow down its creator and origin. Third, collectors rely on classification to gauge rarity and investment potential, as certain movements (like Abstract Expressionism) command premium prices.

1. Historical Timeline Method

The most intuitive way to classify modern art is by dates. While exact cut‑offs vary, most scholars split the period into three phases:

- Early Modern (c. 1860‑1910) - Impressionism, Post‑Impressionism, Fauvism, and early Cubism. Artists broke away from academic realism, focusing on light, color, and subjective perception.

- Mid‑Century (c. 1910‑1945) - Dada, Surrealism, Constructivism, and early Abstract Expressionism. The focus shifted to ideas, the unconscious, and raw, gestural paint.

- Late Modern (c. 1945‑1970) - Pop Art, Minimalism, Conceptual Art, and Op‑Art. Artists reacted to consumer culture, technology, and the aftermath of World War II.

When you date a work-through signatures, materials, or exhibition history-you can immediately narrow down the possible movements.

2. Movement‑Based Classification

Within each chronological slice, distinct movements act as sub‑categories. Below are the most influential ones, each described with its core ideas, typical visual cues, and a flagship artist.

- Impressionism - Loose brushwork, emphasis on fleeting light, everyday scenes. Example: Claude Monet’s "Water Lilies".

- Fauvism - Wild, non‑natural colors, simplified forms. Example: Henri Matisse’s "Woman with a Hat".

- Cubism - Fragmented geometry, multiple viewpoints. Example: Pablo Picasso’s "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon".

- Dada - Anti‑art, absurdity, ready‑made objects. Example: Marcel Duchamp’s "Fountain".

- Surrealism - Dream logic, bizarre juxtapositions. Example: Salvador Dalí’s "The Persistence of Memory".

- Abstract Expressionism - Large gestures, emphasis on the act of painting. Example: Jackson Pollock’s "Number 1, 1949".

- Pop Art - Bright, commercial imagery, irony. Example: Andy Warhol’s "Marilyn Diptych".

- Minimalism - Reductive forms, industrial materials. Example: Donald Judd’s "Untitled (Stack)".

Knowing the visual hallmarks of each movement lets you slot a work even when the date is uncertain.

3. Media & Technique Lens

Modern artists didn’t just change style; they expanded material vocabularies. Classifying by medium adds another useful dimension.

- Painting - Oil, acrylic, watercolor. Most early modern movements used paint as primary vehicle.

- Sculpture - Bronze, steel, found objects. Think of Brâncuși’s streamlined bronzes or later Minimalist steel pieces.

- Photography - Pictorialist to street photography. Artists like Man Ray pushed the camera into Dada territory.

- Printmaking - Lithography, screen‑print. Warhol’s silkscreen approach made Pop Art reproducible.

- Installation & Performance - Site‑specific works, happenings. Examples include Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Rooms (late modern‑era) and Allan Kaprow’s “Happenings”.

- Digital & Video - Early video art (Nam June Paik) and later net‑art. Though technically post‑1970, the lineage starts in the late modern period.

When you identify the medium, you can often pick a compatible movement: a screen‑print points toward Pop, while a welded steel sculpture suggests Minimalism or Constructivism.

4. Geographic & Cultural Context

Modern art wasn’t a monolith; it emerged worldwide.

- Western Europe - Birthplace of Impressionism, Cubism, and Surrealism.

- United States - Hub for Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, and Minimalism.

- Latin America - Mexican muralists (Diego Rivera) and later Neo‑Figurism.

- Asia - Japanese Gutai group (post‑war avant‑garde) and later Japanese Pop (Superflat).

Knowing where an artist worked helps resolve ambiguous cases. A bold, geometric painting from the 1930s could be European Constructivism or American Precisionist-location clarifies which.

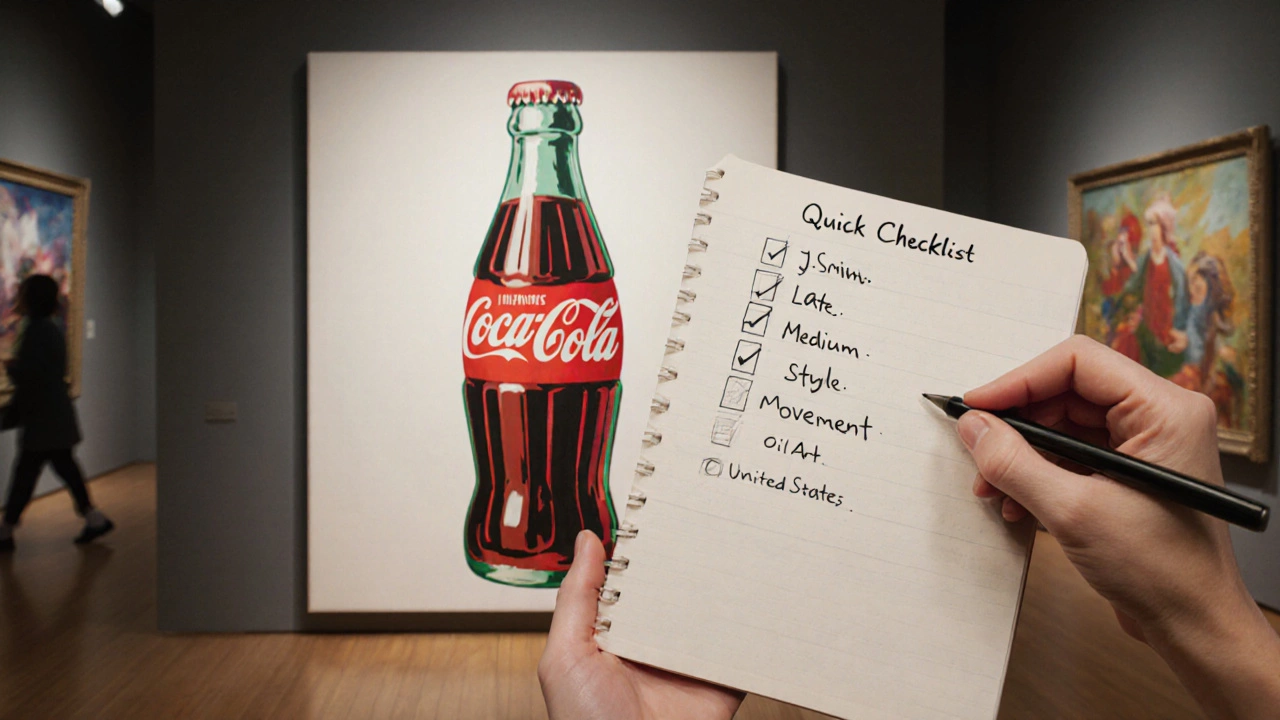

5. Quick Checklist to Classify Any Artwork

- Determine the date or approximate period. Look for signatures, exhibition catalogues, or material aging.

- Identify the medium. Is it oil on canvas, welded steel, or a digital print?

- Observe visual style cues: brushwork, color palette, geometric fragmentation, or commercial imagery.

- Match the style and medium to a movement from the list above.

- Confirm the geographic origin. Artist’s biography or provenance can reveal this.

- Record the classification in a simple label: e.g., "Mid‑Century, Surrealist, Oil Painting, European".

Follow these steps and you’ll have a robust, repeatable classification for any piece you encounter.

Classification Lenses at a Glance

| Criterion | Typical Indicators | Key Movements / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Chronology | Year, exhibition history, material aging | Impressionism (1860‑1880), Abstract Expressionism (1940‑1950) |

| Style | Brushwork, color, composition, abstraction level | Cubism - fragmented planes; Pop Art - bright commercial icons |

| Medium | Paint, sculpture material, photographic process, digital file | Screen‑print - Warhol; Steel sculpture - Judd |

| Geography | Artist’s residence, cultural influences | European Surrealism vs. American Abstract Expressionism |

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

Even seasoned curators stumble. Here are the usual traps and how to sidestep them.

- Over‑relying on date alone. Some late‑Impressionist works overlap with early Fauvism; style matters.

- Assuming a single label. Many pieces are hybrid-think of a Dada collage that also hints at Surrealist dream logic.

- Neglecting provenance. Without ownership history, you might misplace a work geographically.

- Ignoring medium evolution. A digital print from 1995 may still be considered modern if it follows Pop aesthetics.

Putting It All Together: A Real‑World Example

Imagine you encounter a canvas signed "J. Smith, 1953". The surface is flat, colors are flat, and the subject is a repeated Coca‑Cola bottle. Applying the checklist:

- Date: early 1950s - fits Late Modern.

- Medium: oil on canvas.

- Style: flat color, commercial icon - hallmark of Pop Art.

- Geography: research shows the artist worked in New York.

Result: Classified as "Late Modern, Pop Art, Oil Painting, United States". This concise label instantly tells a collector or scholar what to expect.

Final Thoughts

Classifying modern art isn’t about forcing pieces into rigid boxes; it’s about building a flexible framework that respects both historical context and artistic intention. By juggling chronology, style, medium, and geography, you’ll develop a nuanced vocabulary that works in museums, auctions, and everyday conversations.

What time frame does "modern art" cover?

Most scholars define modern art as the period from the late 1860s, when Impressionism broke with academic tradition, to about 1970, when post‑modern ideas began to dominate. The era is usually split into Early Modern (1860‑1910), Mid‑Century (1910‑1945), and Late Modern (1945‑1970).

How can I tell if a painting is Impressionist or Post‑Impressionist?

Impressionism focuses on capturing fleeting light with quick, loose brushstrokes (think Monet’s water lilies). Post‑Impressionism retains the bright palette but adds more structure and personal expression-Van Gogh’s swirling skies are a classic example.

Why do some artworks belong to multiple movements?

Artistic practice evolves. An artist working in the 1950s might blend the flat color of Pop Art with the gestural marks of Abstract Expressionism, creating a hybrid that scholars later label "Pop‑Expressionist". Recognizing overlap helps avoid oversimplification.

Can digital works be considered modern art?

Technically, digital art emerged after the core modern period, but many modern movements anticipated its concepts-think of Dada’s ready‑made objects or Pop’s reproducibility. When a digital piece adopts a modern aesthetic, it can be classified as a late‑modern extension.

What’s the easiest way to start classifying a piece I just found?

Use the quick checklist: note the date, medium, visual style, and where the artist lived. Even a rough label-"Mid‑Century, Surrealist, Oil, European"-gives you a solid starting point for deeper research.