When you walk into a modern art museum and see a painting that looks like a child could’ve made it, you might wonder: how did we get here? Who broke the rules so completely that art stopped being about perfect landscapes and started being about feelings, shapes, and raw truth? The answer isn’t a movement or a group. It’s one man: Paul Cézanne is a French Post-Impressionist painter whose structural approach to form and color laid the foundation for nearly every major 20th-century art movement. Also known as Cézanne, he was born in 1839 in Aix-en-Provence and spent decades painting in quiet isolation, ignored by the art world until his final years.

He Didn’t Paint Like Anyone Else

Before Cézanne, art was mostly about illusion. Artists spent years learning how to make a flat canvas look like a three-dimensional room, a person, or a mountain. They used perspective, shading, and careful brushwork to trick your eye. Cézanne didn’t care. He wanted to show how you actually see things-not how they’re supposed to look.

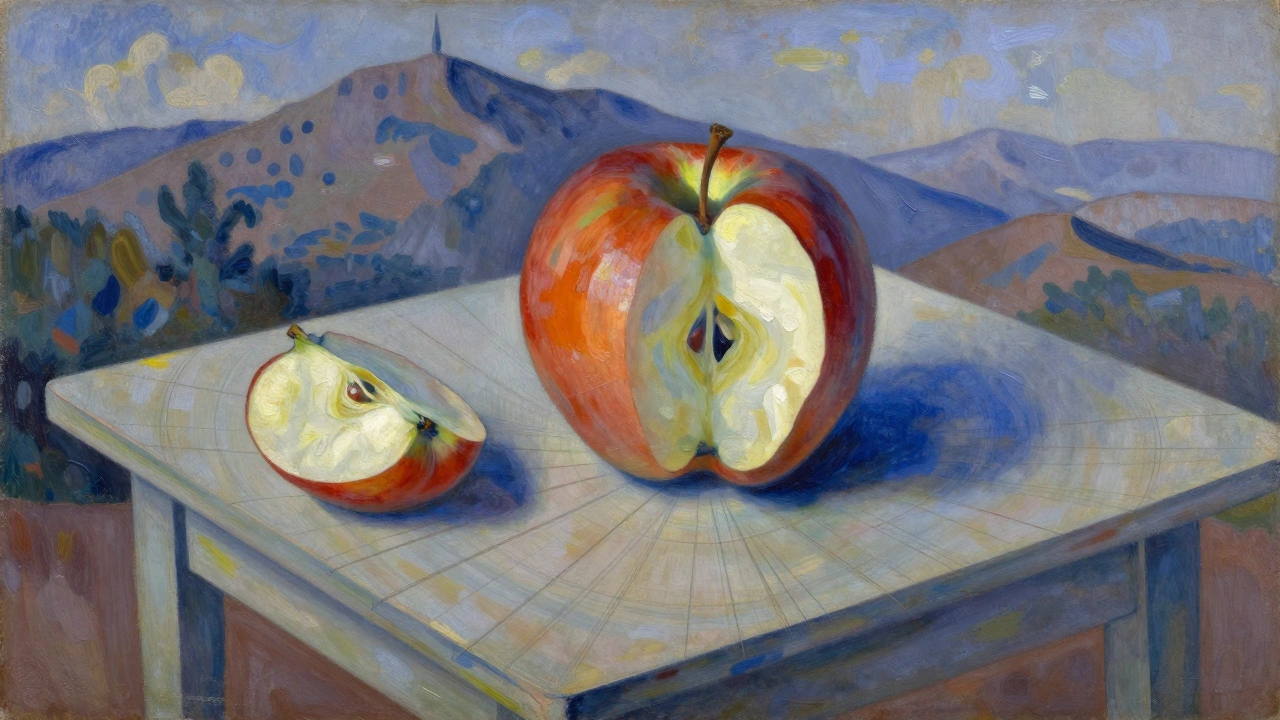

Look at his still lifes. A bowl of fruit? It’s not perfectly round. The table tilts. Apples don’t sit where they should. That’s not a mistake. That’s the point. He painted from multiple viewpoints at once, as if your eyes were moving around the object. He broke the rules of perspective not because he couldn’t draw, but because he wanted to show the truth of perception, not the lie of realism.

His brushstrokes were thick, deliberate, and visible. He didn’t blend colors smoothly. He built forms with patches of color-green next to red, blue next to yellow-letting your eye mix them from a distance. This technique, called constructive stroke, became the blueprint for Cubism. Picasso later said, "Cézanne is the father of us all." He wasn’t exaggerating.

Why Not Monet or Van Gogh?

People often name Monet or Van Gogh as the start of modern art. Monet captured light. Van Gogh poured emotion into color. Both were revolutionary. But they didn’t rebuild the structure of art. Monet’s water lilies are beautiful, but they still sit inside the old framework of perspective and composition. Van Gogh’s swirls are wild, but they’re still about feeling, not form.

Cézanne did something different. He asked: What if we treated a tree like a cylinder? A head like a sphere? A table like a plane? He reduced nature to its basic geometric shapes. That’s not just style-it’s a new way of thinking about reality. It’s the moment art stopped being about what things look like, and started being about what they are.

His influence shows up everywhere. Braque and Picasso took his shapes and shattered them into fragments-creating Cubism. Matisse took his bold color blocks and turned them into pure expression-founding Fauvism. Even abstract artists like Kandinsky, who painted without recognizable objects, were following Cézanne’s lead: if you can break form, why not break subject matter too?

He Was Rejected for Decades

Cézanne wasn’t famous in his lifetime. He was called a "clumsy fool" by critics. The Salon, the most powerful art institution in France, rejected his work over 20 times. He painted in silence, away from Paris, often alone in the hills of Provence. His father, a wealthy banker, disapproved. He wanted Paul to be a lawyer. Paul painted anyway.

He didn’t paint for approval. He painted to solve a problem only he could see: how to make art that felt real without copying reality. He worked slowly. A single painting could take months. He’d stare at a subject for hours, then make one brushstroke. Then wait. Then make another. He didn’t care if people understood him. He just needed to get it right.

By the time he died in 1906, a few younger artists-Picasso, Matisse, Gauguin-recognized him as a genius. After his death, a major retrospective in Paris changed everything. Suddenly, everyone saw what he’d been doing all along. The art world didn’t just change-it exploded.

His Legacy Is Everywhere

Walk into any modern art gallery today, and you’ll see Cézanne’s fingerprints everywhere. The flat planes in Matisse’s interiors. The fragmented faces in Picasso’s portraits. The way color defines space in Rothko’s canvases. Even in abstract expressionism, you can trace the idea back to Cézanne’s belief that structure comes before subject.

His influence isn’t just in painting. Designers use his color relationships. Architects study how he built space with shape. Film directors borrow his compositional tension. His work taught us that meaning doesn’t come from detail-it comes from arrangement, balance, and intention.

He didn’t invent new tools. He didn’t use new materials. He didn’t even invent new subjects. He changed how we look. And that’s the hardest thing to do in art.

What He Actually Said

Cézanne didn’t write books or give lectures. He didn’t write manifestos. But he did speak. And what he said was simple, clear, and profound:

- "I am learning to see."

- "Nature is always the same, but our vision of it changes."

- "Paint from nature, but don’t copy it. Interpret it."

- "Treat nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone."

These aren’t just art tips. They’re philosophical statements. He was saying: reality isn’t fixed. Perception is. Art shouldn’t freeze a moment-it should show how we experience it.

Where to See His Work

If you want to understand why he’s called the father of modern art, you need to see his paintings in person. The Orsay Museum in Paris has over 50 of his works, including The Basket of Apples and The Large Bathers. The Museum of Modern Art in New York owns Mont Sainte-Victoire, his most famous mountain series. The Tate Modern in London and the Philadelphia Museum of Art also hold major pieces.

Don’t just glance. Stand in front of one for five minutes. Watch how the colors shift. Notice how the table leans. See how the fruit seems to float. That’s the moment modern art was born-not in a studio full of people, but in a quiet room, with one man, a brush, and a stubborn refusal to paint the way everyone else did.

Is Paul Cézanne the only person called the father of modern art?

No, but he’s the most universally accepted. Some credit Édouard Manet for breaking academic traditions with works like Olympia. Others point to Delacroix for color or Goya for emotional rawness. But none of them rebuilt the entire language of visual art the way Cézanne did. Picasso, Braque, and Matisse all pointed to Cézanne as their starting point. That’s why he’s the one historians and artists agree on.

Did Cézanne influence non-Western art?

Not directly. But his ideas spread globally through reproduction and exhibitions in the 20th century. Japanese artists like Kansuke Yamamoto and Chinese modernists like Lin Fengmian began incorporating his structural approach after studying European modernism. His emphasis on form over realism resonated with traditional East Asian painting’s focus on essence rather than detail, creating a bridge between cultures.

Why is Cézanne’s work so expensive?

Because he painted slowly, and fewer than 900 finished paintings exist. His most important works are held in major museums. When one appears at auction, collectors fight over it. In 2015, his Les Joueurs de Cartes sold for over $250 million, making it one of the most expensive paintings ever sold. It’s not just rarity-it’s influence. Owning a Cézanne means owning the origin point of modern art.

Can you learn modern art without studying Cézanne?

You can learn techniques without him, but you’ll miss the foundation. Modern art didn’t just happen. It was built. Cézanne gave artists the tools to break from tradition. Without understanding his shift from imitation to structure, movements like Cubism, Fauvism, and even Minimalism seem random. He’s the grammar of modern art. Skip him, and you’re speaking without understanding the language.

What’s the best way to start exploring his work?

Start with The Basket of Apples (1895). It’s small, accessible, and packed with his signature tricks: tilted surfaces, mismatched perspectives, and color as structure. Then move to Mont Sainte-Victoire series-his mountain paintings show how he built space without depth. Finally, try The Large Bathers. It’s complex, monumental, and shows how he turned the human form into architecture. You don’t need to love them. Just look closely. That’s how you begin to see like he did.

Final Thought: He Changed How We See

Modern art isn’t about weirdness. It’s about honesty. Cézanne didn’t paint what he saw-he painted how he saw it. And that’s what made him the father of it all. He didn’t set out to start a revolution. He just kept painting, even when no one understood. In the end, the world had to catch up to him.