Ask ten people if modern art is really art, and you’ll get ten different answers. Some call it genius. Others call it a joke. You’ve seen it-the blank canvas with a single red dot, a pile of bricks in a gallery, a toilet mounted on a pedestal. You’ve probably laughed. Or frowned. Or walked away confused. But here’s the thing: the question isn’t whether it’s pretty. It’s whether it’s art. And that’s where things get messy.

What Even Is Art?

Before we judge modern art, we need to agree on what art means. The old definition? Art is something beautiful, skillfully made, meant to please the eye. Think of Renaissance paintings, Michelangelo’s David, or a detailed portrait. That worked for centuries. But by the late 1800s, photography started stealing the job of capturing reality. If a machine could do that better than a brush, what was left for painters?

Artists didn’t stop making art. They changed what art was for. Instead of copying the world, they started asking questions. What if color could express emotion? What if the idea behind the piece mattered more than how well it was drawn? That shift didn’t happen overnight. It was a slow rebellion. And it led to movements like Impressionism, Cubism, Dadaism, and Abstract Expressionism. Each one broke rules. Each one made people angry. Each one became part of the canon.

Today, art doesn’t need to be skillful in the traditional sense. It doesn’t need to be beautiful. It doesn’t even need to be made by hand. What it needs is intention. A statement. A challenge. That’s why a urinal signed "R. Mutt" by Marcel Duchamp in 1917-called Fountain-is now in the Museum of Modern Art. It wasn’t about the object. It was about asking: Who decides what counts as art?

Why Modern Art Feels Like a Scam

It’s easy to feel tricked. You walk into a gallery. You see a single stripe of paint on a canvas. The price tag says $80,000. You think: My five-year-old could do that. And you’re right. Your five-year-old could. But that’s not the point.

Modern art doesn’t reward technical skill the way classical art did. It rewards context. Timing. Cultural tension. Take Yves Klein’s Anthropometries-naked women covered in blue paint, pressed against canvas like living stamps. At first glance, it looks like a party gone wrong. But Klein wasn’t painting bodies. He was turning the human form into a tool. He was challenging the idea that the artist’s hand must be visible. He was saying: the body can be a brush. The act can be the art.

Or consider Ai Weiwei’s Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn. A photo of him smashing a 2,000-year-old ceramic vase. It’s not beautiful. It’s not even subtle. But it’s powerful. It’s about destruction as protest. About cultural erasure. About value being assigned by institutions, not history. That’s why it’s art. Not because it’s pretty. Because it makes you think.

When people say modern art is a scam, they’re really saying: I don’t understand the rules. And that’s fair. The rules changed. The game changed. But the game still has rules. They’re just not about technique anymore.

The Role of the Viewer

Modern art doesn’t finish when the artist puts down the brush. It finishes when you look at it. That’s the biggest shift from traditional art. In the past, the meaning was locked in. A religious painting told a story. A portrait showed status. Modern art leaves the story open. It asks you to bring your own experience.

Take Mark Rothko’s large, color-field paintings. Just rectangles of soft, glowing color. No figures. No symbols. No hidden messages. People cry in front of them. Why? Because Rothko didn’t paint images. He painted moods. He wanted viewers to feel awe, sorrow, or silence. The painting doesn’t tell you what to feel. It creates space for you to feel something. That’s why two people can stand in front of the same Rothko and have completely different reactions. One sees peace. The other sees emptiness. Both are right.

This is why modern art is often misunderstood. It’s not designed to be decoded. It’s designed to be experienced. If you go to a museum expecting to understand every piece, you’ll leave frustrated. If you go expecting to feel something-even if you don’t know why-you might leave changed.

Money, Fame, and the Art World Machine

Let’s be honest: modern art is expensive. A painting by Jean-Michel Basquiat sold for $110.5 million in 2017. A single sculpture by Jeff Koons sold for $91 million. That’s not about art. That’s about status. Power. Investment. The art world has become a high-stakes game where fame, connections, and marketing matter as much as the work itself.

That doesn’t mean the art is fake. It means the system around it is broken. A lot of modern art gets attention not because it’s profound, but because it’s rare, controversial, or owned by someone famous. The same thing happened with Impressionism in the 1870s. Critics called it unfinished. Dealers refused to show it. Now, it’s in every textbook. The market doesn’t always get it right the first time.

But here’s the catch: the same system that overpays for hype also gives space to artists who have nothing to sell. Performance artists, street artists, digital creators-they don’t need galleries. They don’t need collectors. They just need an audience. And increasingly, they’re finding one online. A TikTok video of a person slowly painting over a city wall can go viral. A digital NFT artwork can be bought for $100,000. The gatekeepers are gone. The definition of art is widening.

Modern Art Isn’t About the Object. It’s About the Idea.

The best way to understand modern art is to stop looking at the thing and start asking: Why was this made?

Take the famous Balloon Dog by Jeff Koons. It’s a giant, shiny stainless steel sculpture of a child’s party balloon. It costs millions. It looks ridiculous. But Koons wasn’t trying to make a balloon. He was trying to make you question why we value things. Why is a cheap plastic balloon worth $5.99, but a steel copy worth $58 million? What makes something valuable? The material? The labor? The fame of the artist? Or just the fact that someone said it was art?

That’s the core of modern art. It doesn’t try to please. It tries to provoke. It doesn’t try to be perfect. It tries to be honest. Sometimes the honesty is ugly. Sometimes it’s boring. Sometimes it’s hilarious. But it’s never neutral.

Modern art asks: What if we stopped measuring art by how well it’s made, and started measuring it by how deeply it makes us question?

Is It Art? The Answer Isn’t Yes or No.

So, can modern art be considered art? The answer isn’t yes or no. It’s: It depends on what you think art is for.

If you believe art should be beautiful, skillful, and timeless-then yes, some modern art fails. But if you believe art should challenge, disturb, reflect, or reveal-then modern art is one of the most powerful tools we have.

Art isn’t a fixed thing. It’s a conversation. And modern art is the loudest voice in that conversation right now. It doesn’t ask you to admire it. It asks you to argue with it. To question it. To sit with it until you either love it, hate it, or realize you don’t know what you thought you knew.

That’s not a scam. That’s the point.

Is modern art just random stuff thrown in a gallery?

No. While some pieces look random, most are the result of years of research, theory, and deliberate choices. Artists like Louise Bourgeois or Gerhard Richter spent decades refining their ideas. What looks like chaos is often carefully structured. The difference is, the structure isn’t about realism-it’s about emotion, concept, or social critique.

Why do museums display things that look like they belong in a landfill?

Museums don’t display trash. They display objects that carry meaning. Take Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines-assemblages of old tires, stuffed animals, and newspapers. These weren’t chosen because they were junk. They were chosen because they represented the clutter of modern life. The museum isn’t saying, "This is art because it’s pretty." It’s saying, "This is art because it makes us see our world differently."

Can anyone call themselves an artist and sell anything as art?

Technically, yes. But that doesn’t mean it will be taken seriously. Art isn’t decided by a single person. It’s decided by a network: critics, curators, historians, collectors, and the public over time. A random doodle on a napkin won’t end up in MoMA. But if that doodle becomes part of a larger conversation-about mental health, identity, or consumerism-it might. The work needs context, not just a signature.

Why is modern art so expensive if it looks easy to make?

The price isn’t for the object. It’s for the idea, the history, and the reputation. A single brushstroke by Jackson Pollock costs millions because it represents a revolution in how we think about creativity. It’s not about how long it took to paint. It’s about how much it changed art forever. Think of it like a first edition of a groundbreaking book-not the paper and ink, but the ideas inside.

Is modern art just for rich people and elites?

It used to be. But now, street art, digital art, and social media have broken those walls. Banksy’s work appears on city walls. Artists like Beeple sell NFTs for millions without ever stepping into a gallery. You don’t need a million dollars to engage with modern art. You just need curiosity. A smartphone. And the willingness to ask: Why does this exist?

What Comes Next?

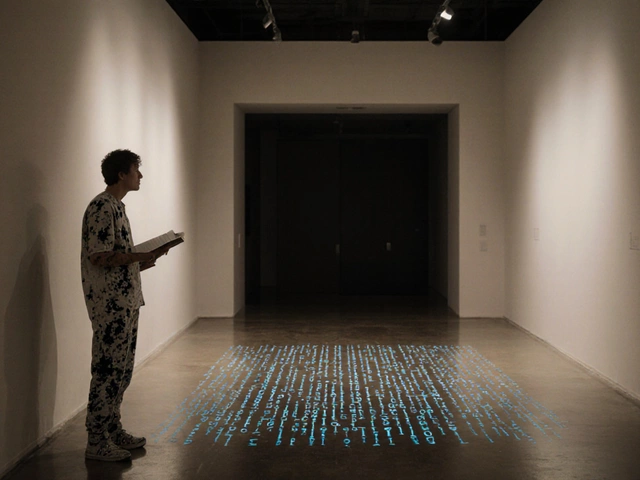

Modern art isn’t going away. It’s evolving. AI-generated images, immersive VR installations, and interactive pieces using biometric data are pushing boundaries even further. The next generation of artists won’t just paint or sculpt. They’ll code, program, and build experiences.

The question won’t be whether it’s art. It’ll be whether we’re ready to see it as art. Because every time the definition of art expands, it’s not because artists got weirder. It’s because we got braver.